When Jacob Elordi stepped into the role of Frankenstein’s creature for Guillermo del Toro’s haunting new adaptation, he didn’t just look to cinema’s history of monsters. Instead, he looked homeward, toward a pair of soft brown eyes and a wagging tail.

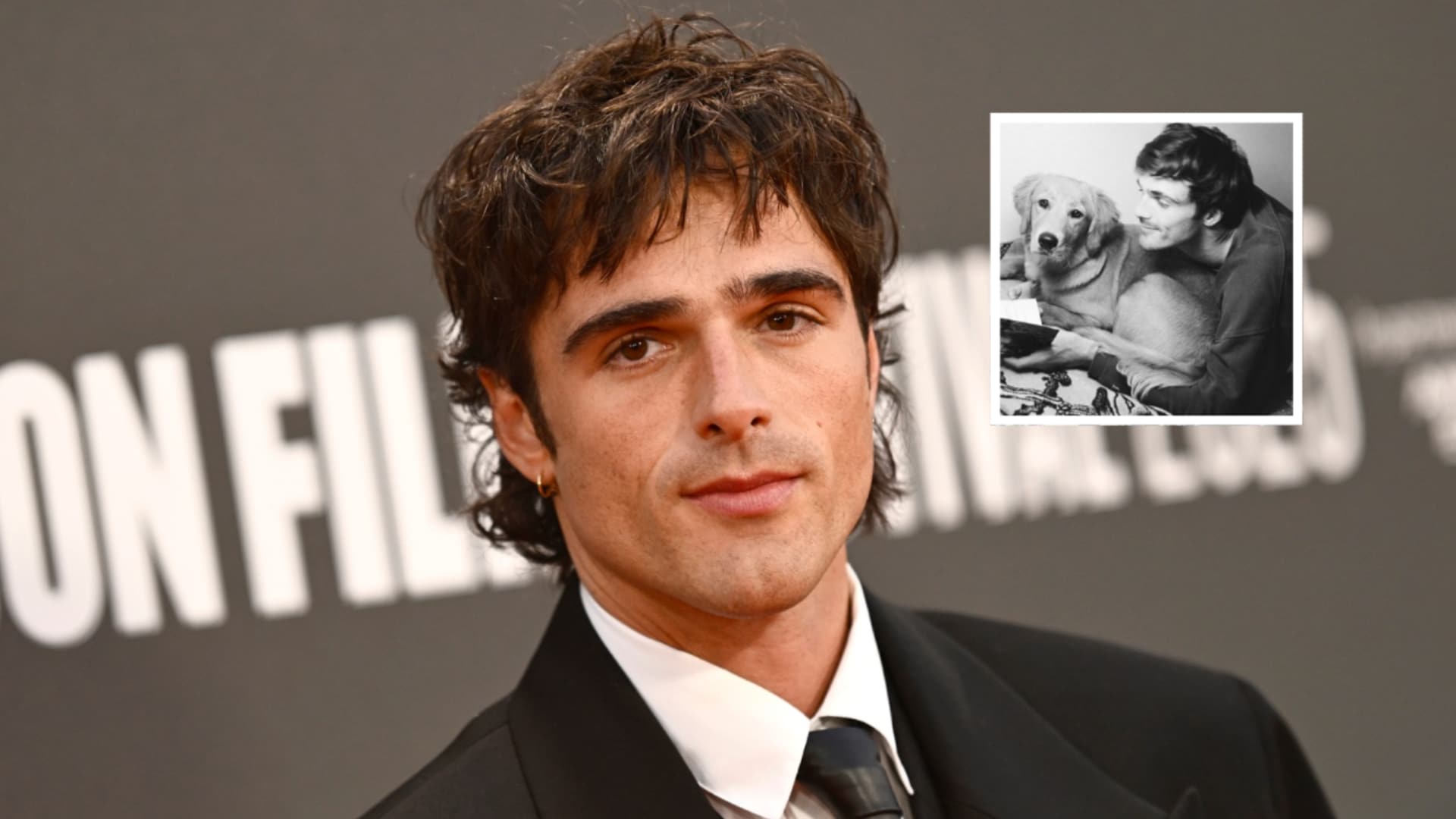

The 'Saltburn' star, now earning rave reviews for his portrayal in 'Frankenstein,' has often credited his golden retriever, Layla, as his emotional compass. But this time, she became his creative muse too.

“I mean, like a child, she doesn't speak, obviously, so everything that she does physically is to sort of get what she needs or to show how she feels,” Elordi told RadioTimes. “So she’s very, sort of, creature-like in the way that she operates in the world. I suppose she's also incredibly sensitive. So there was a lot of that in her – I see the whole world in my dog's eyes.”

For him, that tenderness became essential to his portrayal. “It was very much a big part of myself, I think, in the physicality of the creature,” he said. “It's strange because it's not human, but it almost feels more human than me walking around like a guy!”

Even when fully transformed as the monster, Elordi’s gentleness shone through, as he showed in a behind-the-scenes photo. “She was so sick of me at that point,” Elordi laughed. “She was like, ‘I’m so tired of this and you look weird.’”

On the red carpet at the London Film Festival, Elordi told British Vogue that his four-legged best friend is not just a companion but a guiding force. “I spend most of my time with my dog,” he admitted. “She’s a great teacher in so many ways.”

He went on, “Just in her innocence, how direct she is… I don’t know, my dog is my hero.” Elordi’s interpretation of Frankenstein’s creature emerged from a deep curiosity about what it means to be built from others, yet searching for one’s own soul.

“When I first read the script, I had a lot of ideas about what it means to be constructed of parts,” he told Forbes. “That included things like what it means to have the calf from somebody else, a part of your brain from here, a part of your face from there, and how the communication would work between your brain and the muscles.”

He explored Japanese Butoh dance, a movement art inspired by death and rebirth, and even studied the movements of babies. Yet amid all the cerebral research, one of his most grounding teachers remained Layla.

“My dog has this great innocence in the way that she moves and looks at things,” Elordi said. “There was actually this wonderful moment in the hotel in Toronto just before we started, and I was looking at her thinking, 'What am I going to do?' I was staring at her; she was staring back at me. She walked up to me, and we touched noses, exchanging a little static electricity. I knew then I was okay. It was like she gave me life.”